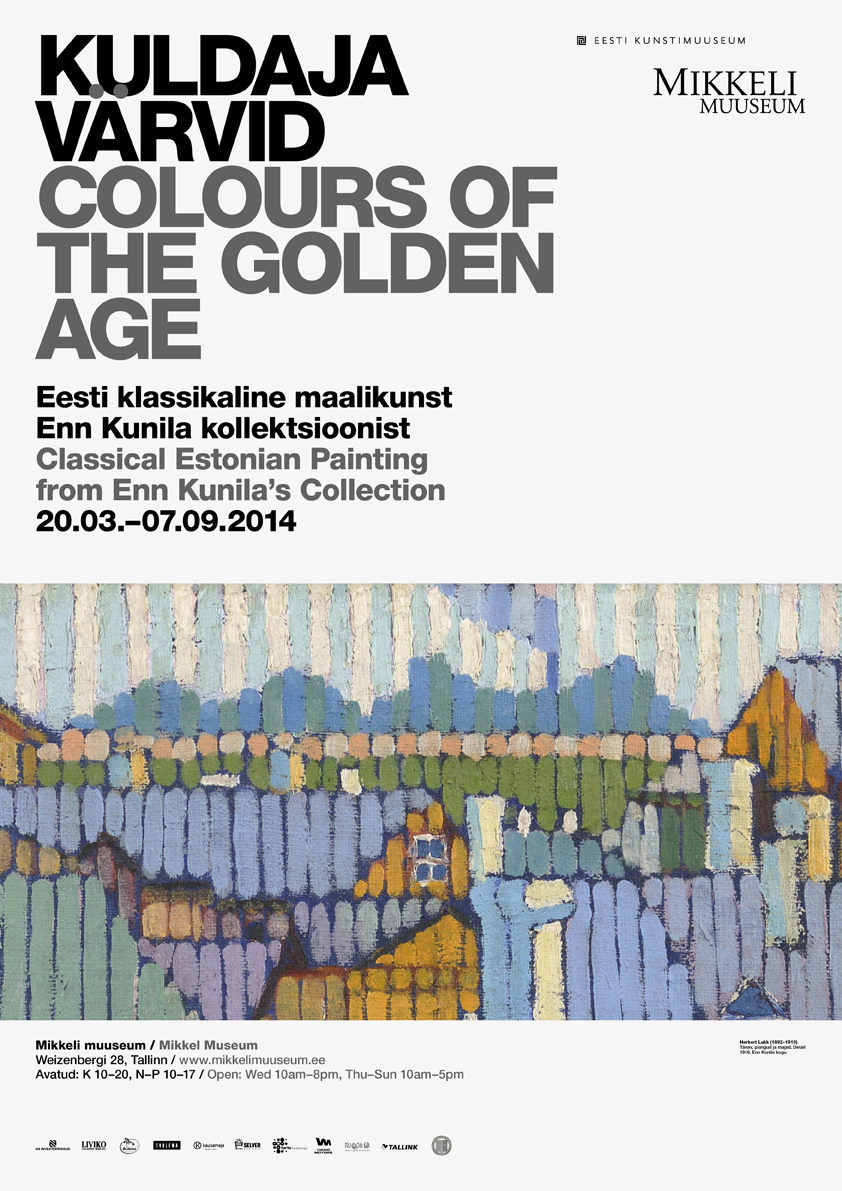

The exhibition „Colours of the Golden Age. Classical Estonian Painting from Enn Kunila’s Collection“ was opened in Art Museum of Estonia Mikkel Museum on 20 March 2014.

The exhibition was opened by Estonian Minister of Foreign Affairs Urmas Paet. Director General of the Art Museum of Estonia Sirje Helme, Director of Kadriorg Art Museum Aleksandra Murre, curator of the exhibition Eero Epner and art collector Enn Kunila introduced the exhibition and newly published catalogue.

The exhibition „Colours of the Golden Age“ focuses on the period 1910-1945.

44 paintings by Konrad Mägi, Nikolai Triik, Ants Laikmaa, Ado Vabbe, Endel Kõks, Richard Uutmaa and many other artists are located on 2 floors of The Mikkel Museum.

The focus is on Estonian landscapes, paintings created by Estonian artists abroad as well as portraits and figural compositions. The exhibition gives an overview of the development of certain trends in Estonian art before the Second World War.

The exhibition comes with an extensive educational programme. Visitors of the exhibition can use interactive media programme – tablet PCs equipped with information about paintings and artists.

The curator of the exhibition is art scientist Eero Epner and the designer is Tõnis Saadoja.

An exhibition album written by Eero Epner and designed by Martin Pedanik was published to mark the exhibition. A colouring book for children by Eero Epner and artist Jaan Rõõmus was also published.

The exhibition will be open until 7 September 2014.

About the exhibition

The title Colours of the Golden Age is most clearly justified in the words of Enn Kunila himself when he says: “The motifs or literary contents of paintings are often discussed but those are not the most determinant aspects for me. Questions concerning composition and colour are far more important, especially a painting’s style or brushing technique.” Kunila has adhered to this principle in choosing works for his collection, the main part of which consists of paintings by Estonian artists completed in the first half of the 20th century. A number of these paintings are on display in these rooms for all to see.

The artworks are divided into four conceptual groups at this exhibition: works completed in Estonia, works created abroad, portraits and figurative paintings, and two paintings connected by a certain Olympian view of the world.

Aino Kallas wrote in her diary in 1908: “Solitude is currently in fashion. People flaunt it like a new neckerchief.” In the first room, we see portraits and figurative paintings, all of which are connected by a certain melancholic attitude. People in these paintings never look straight at the viewer. Instead they have turned their gaze away, gazing somewhere into the vague distance, cutting themselves off from the public: lost in solitude. And when they are shown together in one painting, they are not in contact with each other. Instead, they remain separate, separated from the people who are right there beside them. Sometimes hair hides the face, sometimes the subject’s back is even turned, and sometimes only the subject’s contemplative profile is displayed.

Some believe that melancholy is inherent to Nordic people. Living in darkness causes unfathomable sadness, for instance, but it also affects our perception of the seasons: everything passes, everything is temporal. Sometimes we can get an inkling of the sensitive nervous system of the artist himself. The models in the works of Johannes Greenberg almost always remain silent and turned away. Villem Ormisson and Konrad Mägi, both artists with extremely sensitive, highstrung dispositions, could project their own worlds into the subjects they portrayed.

It is interesting to note that, although the artists were men, they mainly depicted women as melancholic. Most of those women are anonymous, more like objects than animated people, even in the case of some portraits. Thus we see here not so much the melancholy of women as the state of mind of the artists themselves.

Landscape views completed in Estonia and works completed by Estonian artists during their travels are brought together into one hall on the second storey.

The general public is often accustomed to associate works completed in Estonia with Estonia’s national identity. Nowadays, we can look at these works apart from nationalism and, if we like, even in the opposite way: these paintings were rarely associated with personal or community identity for the artists who painted them, since painterly tasks were their primary focus.

“Never, under any circumstances, choose a motif or at least choose as little as you possibly can,” Elmar Kits said. “Because the interesting thing about choosing a motif turns out to be: we choose what we have already definitely seen and what we have already done.” This means: you constantly have to be in motion, surprise yourself with motifs, look for tasks that are interesting from the perspective of the art of painting, which directly contradicts our expectation that the artist has deliberately sought out meaningful motifs of the “Estonian homeland”.

Kits thus formulated a principle of fluidity. You have to walk about and go to new places, not remain stuck where you have already been. Konrad Mägi adhered to exactly the same principle of fluidity. Mägi’s relationship with Estonia was contradictory. “I don’t even want to think about my dear home and homeland – as if I hadn’t even been there. I’m already in my old element of living like a gypsy,” he wrote from Berlin in 1921. Thus it would be going too far to look for intentional searches for identity in Mägi’s works. Even the works he created on Saaremaa, which formed the first complete series of paintings based on motifs of his Estonian homeland, were born more out of painterly interest than a sense of nationalism. Colours, composition, light and touch – these are the important principles, the principles of modernist art.

Eerik Haamer’s Vaika Landscape is an opposite example. Haamer was departing, going away. The Vaika Islands were his last stopover before fleeing from Estonia in 1944 and thus that picture from memory (the painting was created when he was already in Sweden) bears in it a note of seeming optimism, but also a wish to affirm while in exile that he belonged somewhere else. Depicting the landscape of his Estonian homeland was an anchor of existence for Haamer, which he cast out several times more in Sweden: he painted that same motif repeatedly, the last time in the 1980’s, over 35 years after leaving his homeland.

Paul Burman’s Cloudy Day also offers interesting connotations. In 1928, Burman had already been in a mental hospital for several years but with the permission of the chief physician, who was well-disposed towards art, he undertook painting trips (some of which took him as far as Pirita). Cloudy Day was probably painted in the forested park on the grounds of the Seevald Asylum. The dark mass of trees in this work, which cuts off the horizon and interrupts the field of view, and the dramatic clouds allow us to speculate that Burman may have – either intentionally or not – created an image of his state of mind through the landscape in this work, in other words, an image of what formed his distinct identity.

Works of art completed by Estonian artists abroad form the second group in this selection. Living abroad was entirely commonplace for Estonian artists in the first half of the 20th century (as they were impossible for most of the latter half of the 20th century). The world abroad was “normality”, accessible to everyone since even visas were not always required, connections by rail were excellent and not particularly slow (the train ride from Berlin to Paris lasted 17 hours), and even those living in poverty were able to make ends meet. Tuglas recalls that the money obtained from the sale of a postage stamp was enough for two nights at a lodging house in Italy, along with a little money left over for food. Drinking water was available from the public fountains. There was no perceptible distinction back then between “the world abroad” and “Estonia”. One merged into the other. Movement between the two was organic, rapid and commonplace.

The principle of liquidity introduced in these works through walking should also be stressed when considering them. Friedebert Tuglas recalled that he shared in common with Laikmaa, whom he met in Italy, “an important impulse: a great passion for movement and the joy of seeing the things of this world”. Walking and longs trips on foot were not unusual in the cultural scene of those times. Tuglas, for instance, could easily walk for days, covering over 40 versts (more than 40 kilometres) per day. It would be careless to think that this means of movement did not affect people’s creative work.

Thus we see in the case of Laikmaa, Mägi, Vardi, Triik and others how, instead of the posing and fixing of landscape, a sequence of frames much like on a film strip passes before us. Sometimes a random corner or rock that has ended up in a composition betrays the fact that a painting is not an intellectual construction but rather an incidental experience, an interesting emotional or exotic motif discovered while travelling, which in turn provided an impulse for solving different tasks related to painting. That kind of walking in nature, which even took the form of hiking or sporting activity, could be expected from people of peasant descent, requiring strenuous physical exertion. Through one’s sweat, one comes together more with nature, and the distance between oneself and the landscape is eliminated by the lactic acid of one’s muscles. Spending the night in the woods with one’s head resting on moss was not an unusual practice and there is no pictorially clearer image of man and nature becoming one.

Richard Uutmaa’s Fishing Net Menders and Endel Kõks’s View of Tartu form the fourth section at the exhibition. View of Tartu is built up like a pyramid, almost like a temple, heaping up numerous symbolic structures from Tartu of that time, from the Stone Bridge to the Church of St. John, into an imaginary view. Red churches tower at the tip of the pyramid, against the background of a dramatic dark blue sky, giving the entire view an almost religiously solemn dimension. This is an ode to a city, yet we know that Tartu was not just any city for Estonian artists at that time. Tartu was the city. The Pallas School was there. Werner’s Café was there. And although artistic life grew ever more active in Tallinn as well, Tartu was still the city of artists in the 1930s. Thus the painting is a song of praise to a city that has been painted “as their own” by different artists at different times.

Fishing net menders, both men and women, are placed at the heart of Richard Uutmaa’s Fishing Net Menders, and we recognise Uutmaa himself in the figure of one of the men. The low fishing net sheds of the artist’s home village of Altja form an arc surrounding the traditional scene of coastal dwellers at work. The sky threatens thunderstorms, symbolising the approaching catastrophe in this painting completed in 1941. Yet people carry on working here. They do not even notice what is approaching. The lifestyle of country folk is celebrated here, which at that moment was already fading into the past, acquiring ever more exotic and ethnographic value. In the anxious political atmosphere of that era, however, it had less of a sentimental effect than it does today. Fishing Net Menders was more a conscious semi-political act of communication, the creation of a common code between the artist and the public that was read the same way by both, without much getting lost in translation.